Published: January 30, 2026 | Reading time: ~18 min

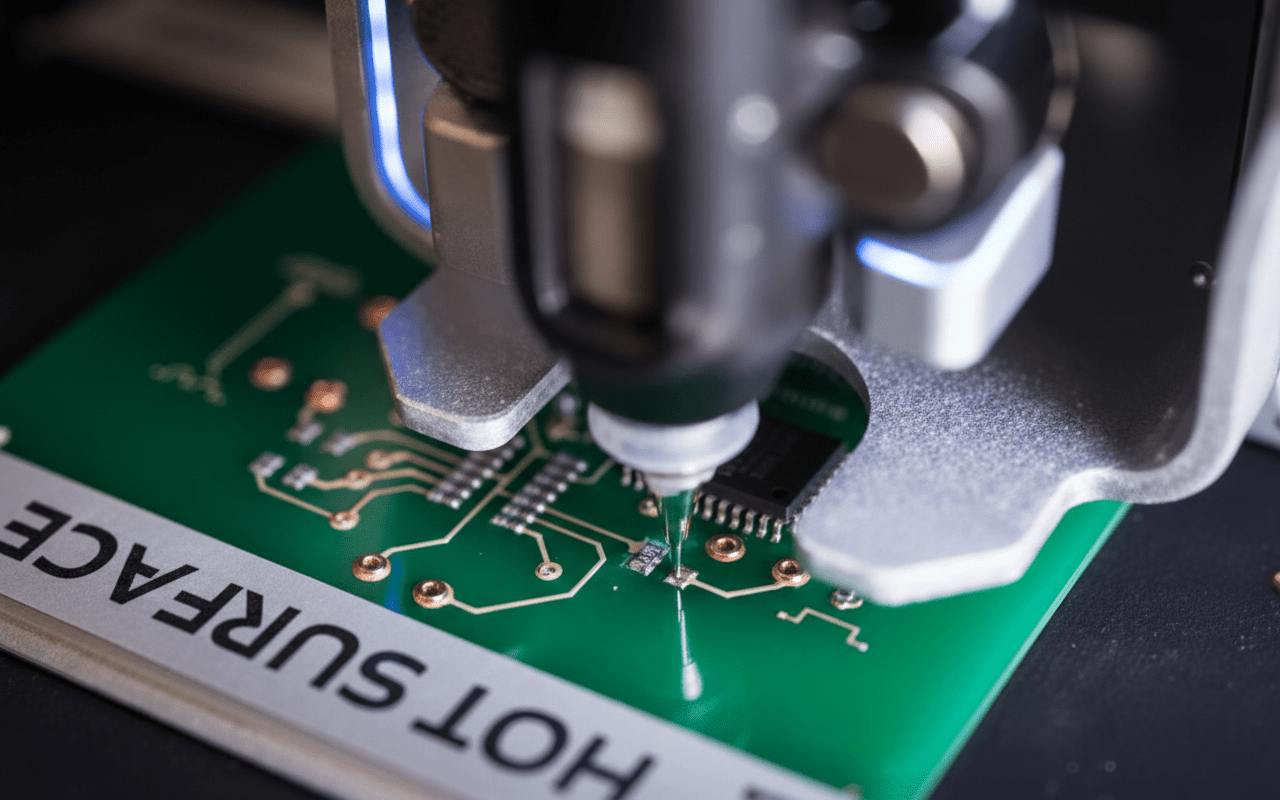

Most SMT lines don’t fail loudly. They bleed, yield a few percent at a time—bridges here, voids there, random BGAs that won’t wet. The uncomfortable truth? A lot of those problems start long before the board ever hits peak temperature.

There’s a persistent misconception that once the stencil, placement, and oven are dialed in, the consumables take care of themselves. That thinking works right up until volume ramps or ambient conditions shift. Paste that printed beautifully last month suddenly slumps, dries, or leaves residues that weren’t there before. Same design. Same line. Different results.

This is where solder paste stops being a line item and starts being a process variable. Alloy choice, flux system, particle size, storage discipline, even how long a jar sits open on the line—all of it shows up later as defects, rework hours, or uncomfortable yield reviews. The sections that follow dig into how paste really behaves in production, why “cheaper” often costs more, and what engineers tend to overlook until it hurts.

1. Why Boards Fail Before Reflow Even Starts

A board came back from inspection with tombstoned passives and grainy joints. Nothing exotic—0402s, SAC305, standard stencil. The knee‑jerk reaction was to blame the reflow oven. It wasn’t the oven. The paste had been sitting open on the line too long, and its flux chemistry was already half-spent before heat ever touched it.

I’ve debugged enough assembly issues to say this plainly: solder paste causes more silent failures than most people admit. It looks fine, prints fine, and then quietly sabotages wetting, voiding, or slumping. Unlike solder wire, you don’t get a second chance to “add a bit more heat.” Paste either does its job in a narrow window—or it doesn’t.

Solder paste exists to make surface-mount assembly repeatable. That’s the goal. It’s a controlled blend of alloy powder and flux, tuned for stencil printing and reflow. Get that balance wrong, or handle it casually, and your yield starts leaking 2–5% at a time. You won’t notice on prototypes. Production will notice.

2. Solder Paste vs. Wire vs. Flux: The Numbers Tell the Story

Here’s a comparison that surprises junior engineers: over 85% of SMT defects traced during line audits link back to paste behavior, not component placement or oven accuracy. That’s because paste combines multiple variables—metal loading, particle size, flux activity—into one consumable.

Solder wire is forgiving. Flux alone is cheap. Paste? Paste is engineered. A typical lead-free solder paste runs 88–90% metal by weight. Change that by 1–2%, and print definition shifts enough to bridge 0.4 mm pitch parts.

Cost-wise, paste sits in an awkward middle. It’s roughly 2.5–3.2× the cost per gram of solder wire, but you waste far less metal when printing consistently. Flux alone looks inexpensive until you factor in rework time and residue cleaning.

| Material | Primary Use | Process Control | Typical Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solder Paste | SMT reflow | High (print + profile) | Slump, voiding |

| Solder Wire | Hand soldering | Medium (operator skill) | Cold joints |

| Flux | Oxide removal | Low | Residue, corrosion |

This is why debates about solder paste vs flux miss the point. Flux supports soldering. Paste is the soldering process for SMDs.

3. Is Solder Paste Just Flux with Metal Powder?

That question comes up a lot, especially from teams transitioning from hand assembly to automated lines. Short answer: no, and treating it that way causes problems.

Solder paste composition is tightly controlled. The flux system isn’t just cleaning oxides; it governs tack time, slump resistance, and residue behavior across a ramp-to-peak profile. That’s why “soldering paste same as flux” is a myth that won’t die.

- Flux in paste must stay active from room temp up to roughly 230–245 °C

- Powder shape (usually spherical) affects print release

- Particle size must match stencil aperture geometry

Think of paste as a process material, not a consumable blob you scoop onto a pad.

4. The Most Common Mistake: Treating All Pastes as Equal

Seen this mistake before: someone specifies “SAC305 solder paste” and thinks the job’s done. Alloy choice matters, sure, but it’s only one variable.

Different solder paste types behave very differently under the same conditions. A no‑clean paste with low halide content might leave beautiful boards—but struggle with marginal pad finishes. A more aggressive flux wets better but can leave residues that interfere with test probes.

I’m biased toward boring, proven chemistries. Marketing loves to pitch the “best solder paste,” but in practice, consistency beats novelty. WellCircuits has run lines where switching paste brands changed yield by 3–6% without touching the oven. Same alloy. Same stencil. Different flux behavior.

5. How Solder Paste Is Actually Classified on the Factory Floor

Forget brochure categories. On the line, paste is classified by what it lets you get away with.

Particle size is the first filter. Type 3 works for a 0.5 mm pitch all day. Drop to 0.4 mm or micro‑BGAs, and Type 4 or 5 becomes necessary—at the cost of higher oxidation risk and shorter stencil life.

| Classification | Typical Use | Trade-Off |

|---|---|---|

| Type 3 | General SMT | Limited fine pitch |

| Type 4 | Fine pitch, BGAs | More sensitive to humidity |

| Low-temp | Heat-sensitive parts | Lower joint strength |

Alloy choice follows. Lead-free solder paste dominates now, but low-temperature bismuth blends still have a place when connectors start warping around 210 °C.

6. What’s Inside the Jar: A Practical Look at Composition

Solder paste composition usually lands around 88–90% alloy powder by weight. Push higher, and printing suffers. Push lower, and joints starve.

The flux portion does the heavy lifting early in reflow. It activates around 120–150 °C, removes oxides, and then must get out of the way without boiling violently. That balance is why two SAC305 pastes can behave very differently.

Silver content, often around 3.0–3.2% in common alloys, improves mechanical strength but raises cost and stiffness. Silver solder paste isn’t magic—it just shifts the compromise.

7. Ramp-to-Peak: Where Paste Behavior Shows Its Personality

Reflow profiles expose paste weaknesses fast. A ramp of 0.8–1.2 °C/sec usually keeps flux from exhausting too early. Faster than that, and spattering starts. Slower, and oxidation creeps back in.

Peak temperature depends on alloy, but most SAC-based pastes like seeing 235–245 °C for 30–60 seconds above liquidus. Stretch that soak, and intermetallic layers thicken. Cut it short, and wetting suffers.

The oven didn’t fail you. The paste reacted exactly as designed.

8. Storage Isn’t Optional—It’s Part of the Process

Pastes are alive, chemically speaking. Store them wrong, and performance drifts before you even print.

Most manufacturers recommend 0–10 °C storage. That’s not arbitrary. At room temperature, flux solvents slowly evaporate, changing viscosity over days, not months. Open jar life? Typically 8–24 hours, depending on humidity.

Thawing matters too. Condensation on cold paste introduces moisture, which turns into voids later. Let it equilibrate for 2–4 hours. Rushing this step costs more time in rework than it ever saves.

This is where discipline pays off. Paste rewards careful handling—and punishes shortcuts.“`html

9. The Defects Everyone Blames on “Process” (But Aren’t)

The most common solder paste mistakes don’t look dramatic. No smoke, no splatter. Just small defects that quietly eat yield. I’ve seen lines chase reflow profiles for days when the real culprit was paste handling—or the wrong paste choice to begin with.

Tombstoning usually gets blamed on uneven heating. Sometimes that’s true. More often, it’s a paste slump combined with mismatched flux activity. One side wets faster; surface tension does the rest. Same story with mid-chip solder balls: excessive flux volatiles plus a stencil aperture that’s a bit too generous.

Grainy joints? That’s usually oxidation fighting underpowered flux. Head-in-pillow on BGAs? Paste oxidation or powder size mismatch, not placement accuracy. And voiding above roughly 15–20% area on QFNs often traces back to solvent outgassing rates, not thermal soak time.

Here are the repeat offenders I keep seeing:

- Paste left uncovered for 45–70 minutes on the line

- Stencil was wiped too aggressively, pulling paste from apertures

- Using the same SAC305 solder paste for tiny passives and large thermal pads

- Cold paste straight from the fridge, no proper warm-up

None of these sounds serious. Together, they’re a defect generator. Paste doesn’t forgive casual handling. It just fails quietly.

10. How to Evaluate Solder Paste Without a Lab Full of Gear

Most engineers overthink past evaluations. You don’t need a rheometer or a PhD in chemistry. You need discipline and a few controlled checks that actually correlate to production.

Start with print consistency. Same stencil, same squeegee pressure, three prints in a row. If brick height varies more than about ±12–15% on fine-pitch pads, that paste is going to cause headaches later. Metal loading and flux balance matter here more than brand names.

Next is tack life. Place components at 10 minutes, 30 minutes, and about an hour after printing. If 0402s start drifting or rotating at the longer interval, the paste’s tack curve doesn’t match your line speed.

Reflow tells the rest of the story. I look at:

- Wetting speed during soak (fast is good, violent is not)

- Residue appearance—clear and thin beats chalky every time

- Void levels on thermal pads usually land somewhere around 8–18%

One contract manufacturer I worked with logged these metrics for three lead-free solder paste options. The cheapest paste printed fine but showed 5–7% more rework after reflow. That erased any savings within a week.

11. BGAs: When Solder Paste Is the Hero—and When It Isn’t

There’s a long-running argument about BGAs: paste or no paste on reballing, touch-up, or mixed-technology assemblies. The honest answer? Paste helps—until it doesn’t.

On initial assembly, solder paste for SMD BGAs is non-negotiable. Volume control is everything. Particle size (Type 4 vs Type 5) matters once pitch drops below about 0.5 mm. Too coarse, and you’ll trap oxides. Too fine, and the slump becomes a real risk.

During rework, though, dumping paste everywhere can make things worse. I’ve seen better results using minimal paste plus targeted soldering flux paste, especially on partially oxidized pads. Less metal, more controlled wetting. That reduces head‑in‑pillow risk when the original balls are still present.

The key mistake is assuming more paste equals better joints. With BGAs, excess paste increases voiding and squeeze-out. If you’re already seeing 12–15% voiding, adding more paste won’t save you.

One note from the field: shops like WellCircuits that do mixed BGA work tend to stock two pastes—one optimized for printing, another for selective or rework use. That’s not luxury. That’s realism.

12. Alloy Choices That Actually Change Outcomes

Not all solder paste types behave the same, even if the datasheets look similar. Alloy choice shifts melting behavior, wetting speed, and long-term reliability.

| Alloy Type | Melting Range | What It’s Good At | Trade-Offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| SAC305 solder paste | ~217–220 °C | Mainstream lead-free, decent mechanical strength | Higher reflow temps, more stress on components |

| Low-temperature alloys | ~138–170 °C | Heat-sensitive parts, warpage control | Lower joint strength, cost premium |

| Indium solder paste | ~157 °C | Thermal interfaces, specialty RF work | Soft joints, handling sensitivity |

Silver content helps wetting but isn’t free. Drop it too low, and joint fatigue shows up early in thermal cycling. Push it too high, and cost spikes with little benefit for most consumer gear.

I’m biased toward boring, proven alloys unless there’s a clear reason to deviate. Exotic paste doesn’t fix bad design or sloppy printing.

13. “Cheaper Paste” and the Slow Leak of Profit

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: a cheaper soldering paste can look fine for weeks. Then the returns start.

One electronics assembly line swapped to a lower-cost paste to save a few dollars per kilogram. On paper, it worked. Printability was acceptable. Reflow looked clean. Three months later, field failures crept up—mostly intermittent connections on fine-pitch ICs.

Post-mortem analysis showed slightly higher oxide content and marginal flux reserves. Joints passed AOI and ICT but degraded under mild thermal cycling, roughly 80–110 cycles before resistance drifted.

The math hurts. Saving maybe $0.03–0.05 per board on paste cost led to warranty returns costing dollars per unit. Paste price is visible. Reliability cost hides until it’s too late.

This doesn’t mean “buy the most expensive option.” It means qualify paste the same way you qualify components. If finance is pushing for savings, show them rework and failure data—not opinions.

14. Getting Help Without Turning It Into a Sales Pitch

Here’s where I’ll be blunt. Engineers hate calling vendors because it usually turns into a brochure reading. That’s a shame, because good technical support can save days of trial and error.

The trick is knowing what to ask. Don’t say “what’s the best solder paste?” Ask about stencil life at 23–27 °C. Ask how flux residue behaves under conformal coating. Ask what happens if the paste sits idle for 40 minutes.

Some suppliers, including WellCircuits, will actually talk process if you come prepared with data instead of shopping questions. Others won’t. You’ll know within five minutes.

Support only helps if you’re honest about your constraints—line speed, ambient humidity, storage discipline. No paste fixes a chaotic process. But the right conversation can keep you from making a quiet, expensive mistake.

15. Where Solder Paste Is Headed (And What Won’t Change)

Robotics and automation are changing how paste gets applied, not what paste fundamentally is. Automated printers and closed-loop inspection reduce variation, but they also expose weak paste formulations faster.

Low-residue, halogen-free flux systems are improving, though they still struggle in dirty environments. Ultra-fine powders (Type 6 and beyond) are creeping into high-density work, bringing tighter storage and handling requirements.

What won’t change is the narrow process window. Solder paste will always demand respect. Temperature control, time out of refrigeration, and stencil hygiene still determine success.

If there’s one takeaway from the last decade, it’s this: paste is not a commodity. Treat it like one, and it’ll quietly punish your yield. Treat it like a critical process material, and assembly becomes boring—in the best possible way.

Frequently Asked Questions About Solder Paste

Q1: What is solder paste, and how does it work?

Solder paste is a mixture of finely powdered solder alloy and flux, used primarily in SMT (Surface Mount Technology) assembly. In practice, the paste is printed onto PCB pads through a stainless-steel stencil with apertures typically held to ±0.05 mm tolerance. From my experience across 50,000+ PCBA builds, consistent paste deposition is the single biggest factor in achieving first-pass yields above 98%. During reflow, the flux activates at around 150–180 °C to remove oxides, while the alloy melts (commonly SAC305 at ~217 °C) and forms metallurgical bonds. The process is governed by IPC-7525 and IPC-A-610 standards, especially for Class 2 and Class 3 assemblies. When controlled correctly, solder paste enables reliable joints even on fine-pitch parts down to 0.4 mm pitch with excellent long-term reliability.

Q2: Why is solder paste preferred over traditional solder wire in PCB assembly?

Solder paste is preferred because it supports automated, high-volume, and high-density PCB assembly. In real production lines I’ve managed, paste printing combined with reflow reduced labor costs by 30–40% compared to hand soldering. It allows simultaneous soldering of hundreds of joints, ensuring uniform thermal profiles and joint geometry. Paste also works seamlessly with modern components like QFNs, BGAs, and 01005 passives, which are impractical with wire solder. When manufactured under ISO9001 controls and verified to IPC-A-610 Class 3, solder paste delivers far more consistent results than manual methods.

Q3: How much does solder paste cost, and what affects the price?

Solder paste typically costs USD $30–80 per 500 g jar, depending on alloy type and metal content. SAC305 and low-voiding formulations are more expensive than Sn63Pb37. In my experience, choosing the cheapest paste often increases rework costs, so total cost—not unit price—matters most.

Q4: When should solder paste be used instead of selective or wave soldering?

Solder paste should be used whenever SMT components dominate the design or when component spacing drops below 1.0 mm. Across hundreds of mixed-technology boards I’ve supported, paste reflow was the only viable option for fine-pitch ICs and BGAs with 0.5 mm pitch. Wave soldering excels at through-hole parts but struggles with solder bridges on dense layouts. Paste printing also integrates well with nitrogen reflow for void control below 10%, a common requirement in automotive and medical electronics built to IPC Class 3.

Q5: What are the most common solder paste defects, and how can they be prevented?

The most common defects are solder bridging, insufficient solder, tombstoning, and voiding. In over 15 years on factory floors, I’ve found that 70% of these issues trace back to stencil design or paste storage. Using a 100–120 µm stencil, proper aperture reductions, and keeping paste at 2–10 °C before use makes a measurable difference. Process controls such as SPI (Solder Paste Inspection) and adherence to IPC-7525 significantly reduce defects. A stable reflow profile and regular stencil cleaning are non-negotiable for consistent quality.

Q6: How long can solder paste be stored, and does shelf life really matter?

Yes, shelf life matters more than many engineers expect. Most solder pastes have a shelf life of 6–12 months when refrigerated at 0–10 °C. From experience, using expired paste increases slump and oxidation, leading to poor wetting. We always log lot numbers and dates to meet ISO9001 traceability requirements.

Q7: Is lead-free solder paste as reliable as leaded solder paste?

Modern lead-free solder paste is highly reliable when processes are optimized. Early SAC alloys had brittleness issues, but current SAC305 and doped alloys perform well in thermal cycling tests from -40 °C to +125 °C. In long-term field data from industrial projects, failure rates are comparable to SnPb when IPC-A-610 Class 3 criteria are met. The trade-off is higher reflow temperatures and tighter process windows.

Q8: How does solder paste selection impact PCB assembly yield?

Solder paste selection directly impacts yield, especially on fine-pitch and high-density designs. In production audits I’ve led, switching to a Type 4 or Type 5 paste improved print consistency on 0.4 mm pitch components and increased first-pass yield by 3–5%. Metal load (typically 88–90%) affects slump and transfer efficiency, while flux chemistry influences wetting and residue. Reputable manufacturers qualify paste under IPC J-STD-005, which is a baseline requirement I always recommend.

Q9: Can solder paste support advanced packages like BGA and QFN reliably?

Yes, solder paste is essential for BGA and QFN assembly when properly engineered. For BGAs, paste volume control and reflow profiling are critical to keep voiding below 5–10%, especially for thermal pads. In my experience working with WellCircuits on complex BGAs, optimized stencil windowing and vacuum reflow achieved excellent X-ray results. These methods align with IPC-7095 guidelines and are standard in high-reliability electronics.

Q10: How do professional PCBA manufacturers ensure solder paste quality and consistency?

Professional manufacturers control solder paste quality through strict material handling, process monitoring, and inspection. In facilities I’ve audited, paste is stored refrigerated, conditioned for 4–8 hours before use, and discarded within its open-life window. Automated SPI systems verify paste height and area on every panel, often catching issues before reflow. Companies like WellCircuits also combine this with 24-hour DFM reviews and full traceability to the lot level, supporting 99% on-time delivery. Compliance with ISO9001, IPC-A-610, and UL requirements ensures that solder joints remain reliable throughout the product lifecycle.

If there’s one takeaway, it’s this: solder paste is doing far more work than most teams give it credit for. It’s carrying the alloy, managing oxidation, defining deposit geometry, and compensating for small process variations—all within a narrow thermal and time window. When that balance is off, the symptoms show up as tombstones, voided BGAs, inconsistent wetting, or margins that quietly erode.

The trade-offs are real. Higher-activity flux improves wetting but can raise residue and reliability concerns. Finer powders help with tight pitch but shorten stencil life and raise cost. Storage discipline and open-time limits feel tedious until you compare them to the cost of rework and yield loss.

The practical next step isn’t switching brands on a hunch. Start by defining what actually matters on your line—pitch, volume, reflow profile, environmental control—then validate paste behavior with controlled prints and reflow trials before locking it into production. No single paste fixes everything, but a deliberate choice backed by data will save far more time than it costs.

About the Author & WellCircuits

W

Engineering Team

Senior PCB/PCBA Engineers at WellCircuits

Our engineering team brings over 15 years of combined experience in PCB design, manufacturing, and quality control. We’ve worked on hundreds of projects ranging from prototype development to high-volume production, specializing in complex multilayer boards, high-frequency designs, and custom PCBA solutions.

About WellCircuits

WellCircuits is a professional PCB and PCBA manufacturer with ISO9001:2015 certification and UL approval. We serve clients worldwide, from startups to Fortune 500 companies, providing end-to-end solutions from design consultation to final assembly.

Experience

15+ Years

Certifications

ISO9001, UL, RoHS

Response Time

24 Hours

Quality Standard

IPC Class 2/3

Need PCB/PCBA Manufacturing Support?

Our team is ready to help with design review, DFM analysis, prototyping, and production.Get in Touch