Published: February 03, 2026 | Reading time: ~18 min

Most engineers think that if the schematic checks out and the board passes bench tests, the job’s done. That assumption causes more field failures than bad firmware ever will. Once heat, vibration, and tolerance stack-ups enter the picture, the weak points show up fast—and they usually sit around the IC.

Integrated circuits don’t live in isolation. They pull current in bursts, dump heat into copper, stress solder joints during thermal cycling, and interact with nearby passives in ways simulation rarely captures perfectly. I’ve seen solid designs unravel simply because the IC package choice didn’t match the enclosure temperature, or because aging effects on surrounding components were ignored.

This is why understanding ic board components as a system matters. Not just what an IC is on a circuit board, but how it behaves over time, how it’s supported by passives, and how the PCB itself becomes part of the component. The sections ahead walk through IC types, packaging, board-level interactions, aging, and the real differences between IC boards and generic PCBs—without pretending there’s a single “best” answer. Even experienced teams, including ones I’ve crossed paths with at WellCircuits, relearn these lessons the hard way.

1. When a Board “Works” on the Bench but Fails in the Field

A control board came back from testing with no obvious faults. Power rails were clean. Signals looked fine. Two weeks later, the same design started resetting randomly once installed inside a metal enclosure. The culprit wasn’t firmware. It wasn’t EMI. It was a poor understanding of IC board components and how they behave once real-world heat, vibration, and tolerances stack up.

This is the part most newcomers miss when asking what an IC is on a circuit board. An IC isn’t just a chip you drop onto copper. It’s a thermal source, a mechanical stress point, and often the most sensitive component on the board. How that IC interacts with nearby passives, copper pours, vias, and even solder mask openings matters more than people want to admit.

IC boards—sometimes casually called IC boards—are PCB assemblies designed specifically around integrated circuits. The routing density, component spacing, and layer stack-up usually exist because the IC demands it. High pin-count parts force fine traces. Power ICs demand low-impedance planes. Mixed-signal ICs hate sloppy grounding. Ignore those needs, and the board may pass basic tests but fail after a few thermal cycles around 70–85°C.

I’m biased here: if you don’t start your design thinking from the IC outward, you’re already behind.

2. Why IC Boards Dominate Modern Electronics (and the Numbers Back It Up)

Look at teardown data from consumer electronics over the last decade. Discrete component counts per function dropped sharply, while IC density climbed. A power management function that once needed 12–18 discrete parts now fits inside a single QFN with four capacitors around it. Board area savings typically land in the 35–55% range, depending on layout discipline.

Industrial electronics followed the same path, just more cautiously. In factory automation and robotics, IC boards replaced relay-heavy designs because repeatability and size mattered. Yield data from mid-volume runs (a few hundred units) often shows 3–6% higher first-pass yield when logic and control functions are IC-centric rather than discrete-heavy. Not magic—just fewer solder joints and fewer failure points.

Power efficiency is another driver. Integrated solutions usually shave 8–15% off losses compared to older discrete designs, assuming layout isn’t sloppy. That translates into real thermal headroom: junction temperatures dropping around 28–34°C in enclosed systems.

| Design Approach | Board Area | Assembly Risk | Thermal Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete-heavy | Larger, loosely packed | Higher (many joints) | Harder to manage |

| IC-centric board | More compact | Lower, but denser | Predictable if designed well |

This shift is why manufacturers like WellCircuits see far more questions about IC placement, grounding, and heat spreading than about basic resistor sizing. The bottleneck moved.

3. What Exactly Is an “IC Board,” Anyway?

People ask what the IC board is as if it’s a special product category. It isn’t. An IC board is simply a PCB where integrated circuits are the primary functional elements, not supporting actors.

In most cases, that means tighter tolerances, more layers, and more attention to power integrity than a simple through-hole board. The IC defines the rules; everything else follows.

- High pin-count ICs drive trace width and spacing limits

- Fast-switching ICs dictate plane continuity and decoupling strategy

- Precision ICs force better control of noise and leakage

4. The Most Common Mistake: Treating All ICs the Same

Here’s a mistake I still see: designers grouping ICs as if they’re interchangeable blocks. They’re not. A microcontroller, a switching regulator, and an op-amp may sit side by side, but they want very different environments.

Switching regulators inject noise. Put them too close to sensitive analog ICs, and you’ll chase phantom bugs for weeks. High-speed digital ICs care about impedance control; analog ICs care about leakage and ground cleanliness. Lumping them together without zoning is lazy design.

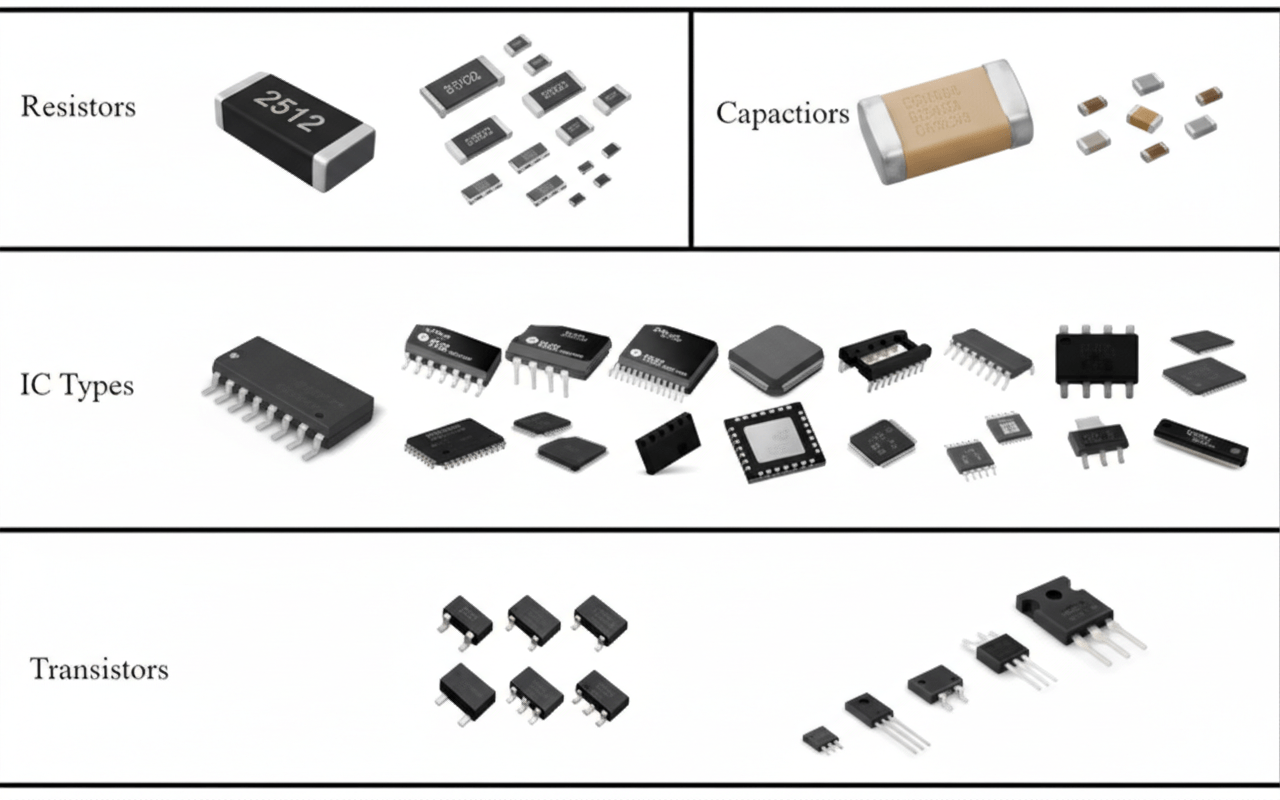

This is where circuit board component identification becomes more than labeling parts. You’re identifying behavior. Active components—ICs, transistors, diodes—interact dynamically. Passive parts mostly react. Mixing them without intent is how marginal designs happen.

I’ve debugged boards where nothing was “wrong” per the schematic. Layout ignorance was the real defect.

5. Inside an IC: Why the Black Package Deserves Respect

Crack open an IC package (don’t do this unless it’s already dead), and you’ll find a silicon die bonded to a lead frame with wires thin enough to snap if you breathe wrong. Those bonds are why mechanical stress and thermal expansion matter.

The die itself is layered—transistors, interconnects, passivation—all optimized for electrical performance, not kindness to your PCB. When the board flexes or cycles between 20°C and 90°C repeatedly, that stress transfers through the package. Usually it’s fine. Sometimes it isn’t.

That’s why large ICs on thin boards crack solder joints before smaller passives do. It’s also why underfill shows up in higher-reliability designs. Underfill adds cost and complicates rework, but it spreads stress. Trade-offs everywhere.

6. IC Packages and What They Mean for Layout Reality

The package is the negotiator between silicon and PCB copper. Choose poorly, and no amount of routing skill will save you.

SOICs are forgiving. BGAs are not. QFNs look simple, but punish bad thermal design. Each package choice affects inspection, rework, and yield.

| Package Type | Pros | Cons | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOIC/SOP | Easy inspection, reworkable | Larger footprint | Low to mid-density control |

| QFP | Many pins, visible leads | Fine pitch routing | MCUs, DSPs |

| BGA | High density, good signal integrity | X-ray needed, cost | High-performance logic |

Forget the marketing slides. Package choice should follow your fab’s capability and your volume. Not every shop loves BGAs, even if they say they do.

7. ICs Within the Bigger Picture of Board Components

An IC board isn’t just ICs. It’s an ecosystem. Power conditioning, signal shaping, and protection—all handled by surrounding parts that don’t get enough respect.

Passives are usually passive until they fail. A cheap capacitor with a marginal voltage rating will age faster next to a warm IC. Inductors saturate. Resistors drift. None of this shows up in a tidy schematic.

When doing PCB board component identification, I mentally rank parts by risk. ICs sit at the top, but their supporting cast determines how long they behave. Skimp there, and you shorten the IC’s useful life without ever touching the chip itself.

8. Where IC Boards Actually Earn Their Keep

IC boards show their value in places where consistency matters more than brute force. Industrial automation, medical monitoring, robotics—these systems need repeatable behavior over thousands of cycles.

In factory automation, IC boards handle timing, sensing, and control loops that used to require racks of hardware. In medical electronics, integration reduces size but raises the bar for reliability. One noisy ground can ruin a measurement.

Consumer electronics get the spotlight, but industrial users are often the harshest critics. They don’t care if the board looks clever. They care if it still works after years of temperature swings, vibration, and marginal power. That’s where good IC board component choices quietly prove themselves.

Shops like WellCircuits tend to see this split clearly: consumer designs push density; industrial designs push discipline. Different pressures, same fundamentals.

9. Designing Around the IC, Not Just Placing It

The most common mistake I still see? Treating IC placement like Lego. Drop the chip, route the pins, move on. That approach ignores how IC board components actually behave once power, heat, and time get involved.

At the silicon level, an IC is planned long before your PCB exists. Power domains, internal clocks, IO banks, and thermal paths are already baked into the package. Your job at the board level is to respect those assumptions. Miss them, and you get boards that pass the functional test but fall apart after a few months.

Take power delivery. A modern MCU or SoC might tolerate a few tens of millivolts of ripple at the core pin. On the bench, your scope probe says it’s fine. In the enclosure, after 40–60 minutes at around 75°C, that ripple creeps up. Why? Decoupling caps too far away, vias with too much inductance, or ground return paths that snake around like spaghetti.

I’m blunt about this: if your schematic symbol doesn’t reflect how the IC is internally organized, you’re guessing. Pin groups matter. Ground pins aren’t interchangeable. Analog reference pins don’t want to share copper with a switching regulator return. Forget what the simplified app note shows—read the package pin description and design outward from there.

10. Aging Is Real: How IC Board Components Change Over Time

Boards don’t usually die suddenly. They drift, degrade, and then cross a line.

In field returns I’ve looked at, outright silicon failure is rare before 8–12 years unless the environment is harsh. What fails first are the supporting IC board components: electrolytic capacitors drying out, solder joints micro-cracking, and connectors oxidizing. Once those go, the IC gets blamed even though it’s just reacting to bad conditions.

- Capacitors: Aluminum electrolytics lose capacitance slowly, sometimes 15–30% over a decade at elevated temperatures.

- Solder joints: Lead-free alloys are stiff. After a few hundred thermal cycles between 20°C and 80°C, cracks can start at high-mass IC pads.

- Semiconductors: ICs themselves age mostly due to electromigration and hot carrier effects—usually a late-life problem.

You can’t stop aging, but you can slow it down. Higher-grade materials help. Better thermal spreading helps more. I’ve seen the same IC circuit board last twice as long simply by lowering the average operating temperature by roughly 8–12°C. That’s not magic. That’s physics.

11. IC Board vs. PCB Board: Clearing Up the Confusion

This question keeps popping up in emails: What is an IC board, and how is it different from a PCB?

An IC is a single integrated circuit—silicon, packaged, sealed. A PCB is the physical platform: fiberglass, copper, vias. An “IC board” isn’t a formal standard term. It’s shorthand engineers use for a PCB designed primarily around one or more critical ICs.

Here’s why the distinction matters. In simple boards, ICs are passengers. In dense designs—power management, RF, mixed-signal—the IC is the driver. Layer count, impedance control, and even board thickness often exist because of that chip.

If you’re doing PCB board components identification and wondering why one board costs three times more than another, look at the IC requirements. Fine-pitch BGAs, controlled impedance, blind vias—all of that adds cost fast. The IC didn’t just influence the board. It dictated it.

12. Passive Components: The Quiet Partners That Make or Break ICs

Resistors, capacitors, inductors. Boring? Only until they’re wrong.

Passives don’t get marketing hype, but they quietly determine whether an IC behaves or misbehaves. A 0.1µF decoupling capacitor isn’t just “0.1µF.” Dielectric type, voltage rating, package size, and DC bias behavior all matter. I’ve measured ceramic caps losing over half their effective capacitance under bias. The schematic didn’t lie—the physics did.

Placement matters as much as value. A bypass cap 12 mm away from an IC pin might as well be decorative at high frequencies. Inductors saturate. Resistors drift with temperature. None of this shows up in ideal simulations.

One practical rule I stick to: spend time on passives closest to the IC, loosen up farther away. That’s where real stability comes from.

13. Active Components Beyond the Main IC

People talk about “the IC” as if it works alone. It doesn’t.

Transistors, regulators, level shifters, drivers—these active devices shape how the main IC experiences the world. A marginal LDO can inject noise straight into a sensitive ADC. A MOSFET with slow gate drive can cook itself and heat the board under the IC.

Active parts also introduce failure modes that look like firmware bugs. A drifting reference voltage, a leaky transistor at high temperature, a protection diode clamping when it shouldn’t. Seen all of those. Debugging them is miserable if you don’t consider the entire active ecosystem around the IC component.

14. Cost Reality: IC Board Price Isn’t Just About the Chip

Here’s an uncomfortable truth: asking for an ic board price without context is meaningless.

Yes, people search for things like 7297 IC board price or 7265 IC board price. What they usually get is a number that ignores volume, layer count, material, and test coverage. The IC itself might be $4–$12 in moderate volume. The board built properly around it can cost more than the silicon.

| Cost Driver | Typical Impact |

|---|---|

| Layer count | 4-layer vs 8-layer can double bare PCB cost |

| Fine-pitch ICs | Tighter yield, more inspection time |

| Testing | ICT + functional test adds real labor cost |

I lean toward simpler boards unless performance truly demands complexity. Overengineering hurts budgets faster than most engineers expect.

15. Practical Wrap-Up: How to Think About IC Board Components Going Forward

If you’re still asking what an IC is on a circuit board, that’s fine. Everyone starts there. The next step is understanding relationships.

IC board components aren’t independent. Thermal design affects electrical stability. Passive selection influences signal integrity. Mechanical stress shows up as electrical failure six months later. Once you see those links, circuit board component identification stops being a memorization exercise and becomes a system-level skill.

I’ve worked with teams who learned this the hard way—and others who got it right early. The difference wasn’t the tools. It was a mindset.

For sourcing and fabrication, most engineers I know cross-check notes from fabricators like WellCircuits alongside datasheets and IPC standards, then make conservative choices where it matters. That habit saves more redesigns than any fancy simulation.

Define the IC’s real needs. Design the board to support them. Then question every shortcut. That’s how IC circuit boards survive the field, not just the lab.“`html

Frequently Asked Questions About IC Board Components

Q1: What are IC board components and how do they work?

IC board components refer to integrated circuits and their supporting parts—such as resistors, capacitors, and connectors—mounted on a printed circuit board to perform specific electronic functions. In over 15 years and 50,000+ PCB/PCBA projects, we’ve seen that proper IC selection and placement directly impact performance and yield. Technically, ICs are soldered onto pads with tolerances typically within ±0.05 mm, connected by copper traces as fine as 0.1 mm. These components work together to process signals, manage power, or control logic based on the circuit design. From an industry standpoint, quality builds follow IPC-A-600 Class 2 or Class 3 standards depending on reliability requirements. A well-designed IC board also goes through DFM and DFA checks—often within 24 hours—to ensure manufacturability and assembly reliability. When done correctly, failure rates stay below 0.3% in mass production, which is a benchmark we consistently aim for.

Q2: Why are IC board components critical in modern electronics?

IC board components are critical because they enable high functionality in compact form factors. Based on real production data from thousands of consumer and industrial boards, integrated circuits can reduce overall BOM count by 30–60% compared to discrete designs. This improves signal integrity, lowers power consumption, and increases reliability. From an expertise perspective, modern ICs support high-density layouts with BGA or QFN packages, often requiring 4–8 layer boards and controlled impedance traces. Industry standards like IPC-2221 guide these designs, while ISO9001-certified processes ensure consistency. Simply put, without properly designed IC board components, achieving today’s performance, size, and cost targets would be nearly impossible.

Q3: How much do IC board components typically cost?

Cost varies widely depending on IC type, package, and volume. In practice, simple MCUs may cost $0.50–$2 in volume, while advanced processors can exceed $20. From our experience, smart component selection and early BOM optimization can reduce total board cost by 10–25% without sacrificing reliability.

Q4: When should you use advanced IC board components instead of discrete components?

You should use advanced IC board components when size, performance, or power efficiency is critical. In industrial and automotive projects we’ve handled, switching from discrete logic to integrated ICs reduced board area by up to 40%. Technically, ICs offer tighter parameter control, often within 1–2% variation, compared to wider tolerances in discrete designs. They also simplify assembly, which improves yields under IPC-A-610 acceptance criteria. However, they require stricter layout rules and thermal management. For high-volume or performance-driven products, IC-based designs are almost always the better long-term choice.

Q5: What quality standards should IC board components meet?

High-quality IC board components should comply with recognized industry standards. In our production lines, we typically build to IPC-A-600 Class 2 for commercial products and Class 3 for medical or aerospace applications. Components should be UL certified where safety is involved and sourced from ISO9001 or IATF16949 approved suppliers. From hands-on experience, boards meeting these standards show 20–30% fewer field returns. Electrical testing, AOI, and X-ray inspection for BGA ICs are also essential to ensure long-term reliability.

Q6: What are common problems with IC board components?

The most common issues include solder joint defects, thermal stress, and signal integrity problems. In real-world analysis, over 60% of IC-related failures trace back to poor layout or inadequate reflow profiles. Following IPC reflow guidelines and proper stack-up design eliminates most of these risks.

Q7: How do you ensure reliability in ic board component assembly?

Ensuring reliability starts at design and continues through assembly and testing. From more than 50,000 assembled boards, we’ve learned that proper land pattern design and controlled impedance routing are non-negotiable. Assembly-wise, we use automated pick-and-place machines with ±0.03 mm accuracy and reflow profiles tailored to each IC’s datasheet. X-ray inspection is mandatory for BGA and QFN packages to verify hidden solder joints. Reliability testing often includes thermal cycling from -40 °C to +85 °C and burn-in for 24–72 hours. Standards like IPC-A-610 and JESD22 guide acceptance criteria. At WellCircuits, these controls help us maintain over 99% on-time delivery and consistently low RMA rates.

Q8: How do IC board components compare with module-based solutions?

IC board components offer more design flexibility and lower long-term cost compared to off-the-shelf modules. In our experience, module-based designs can speed up prototyping but often increase BOM cost by 20–50% in production. IC-level designs allow tighter integration, better thermal control, and easier compliance with IPC and EMC standards. However, they require stronger engineering capability and longer initial development. For scalable products, discrete IC board designs usually provide better ROI over time.

Q9: Are IC board components suitable for low-volume prototypes?

Yes, they are suitable, but with trade-offs. For low-volume builds under 100 units, IC board components may increase NRE and setup costs. That said, in many prototype runs we’ve supported, early IC integration reduced redesign cycles and saved months in development time.

Q10: How can manufacturers reduce risks when sourcing IC board components?

Risk reduction starts with supplier qualification and design validation. Based on years of sourcing experience, using authorized distributors and checking lifecycle status can prevent sudden shortages. Technically, designing footprints with alternate package options adds flexibility. A 24-hour DFM review and BOM check—something teams like WellCircuits routinely provide—can catch issues before fabrication. Compliance with ISO9001 processes and traceable component batches further improves trust and long-term supply stability.“`

IC boards don’t fail because an integrated circuit exists—they fail because the board around it doesn’t respect what that IC needs over time. Package choice affects thermal stress. Passive placement influences noise margins. Aging quietly shifts values until margins disappear. None of these issues is dramatic on day one, which is exactly why they’re missed.

The practical takeaway is simple but uncomfortable: stop thinking of ICs as drop‑in parts. Treat them as the center of a small ecosystem that includes copper weight, via strategy, passives, enclosure temperature, and expected service life. When evaluating IC board components, start by defining operating temperature ranges and lifetime expectations, then work outward to package type, layout density, and supporting devices. Prototype under realistic conditions, push boards through thermal cycles, and assume something will drift—because it will. Designs that survive the field usually aren’t clever; they’re honest about physics and disciplined about trade-offs.

About the Author & WellCircuits

W

Engineering Team

Senior PCB/PCBA Engineers at WellCircuits

Our engineering team brings over 15 years of combined experience in PCB design, manufacturing, and quality control. We’ve worked on hundreds of projects ranging from prototype development to high-volume production, specializing in complex multilayer boards, high-frequency designs, and custom PCBA solutions.

About WellCircuits

WellCircuits is a professional PCB and PCBA manufacturer with ISO9001:2015 certification and UL approval. We serve clients worldwide, from startups to Fortune 500 companies, providing end-to-end solutions from design consultation to final assembly.

Experience

15+ Years

Certifications

ISO9001, UL, RoHS

Response Time

24 Hours

Quality Standard

IPC Class 2/3

Need PCB/PCBA Manufacturing Support?

Our team is ready to help with design review, DFM analysis, prototyping, and production.Get in Touch