Published: January 19, 2026 | Reading time: ~14 min

Summary: Flex PCBs solve problems rigid boards can’t, but cost and design trade-offs matter. See how a flex PCB manufacturer fits real-world builds.

The failure usually isn’t electrical. It’s mechanical. A board passes bench tests, works fine at room temperature, but then starts failing once vibration, bending, or thermal cycling is introduced. Connectors loosen, cables fatigue, and suddenly the PCB itself isn’t the weak point anymore—the way everything is connected is.

That’s where flexible circuits tend to show up, often after at least one redesign. Flex PCBs aren’t just thinner or bendable versions of FR-4. They behave differently under stress, they age differently, and they force different decisions around copper weight, stack-up, and assembly. Teams that treat them like rigid boards with a twist usually learn the hard way.

Working with the right flex pcb manufacturer changes that dynamic. Questions about bend radius, static versus dynamic flexing, or why a coverlay opening matters don’t come from theory—they come from yield loss and cracked copper seen before. The sections ahead dig into how flex and rigid-flex circuits are built, where the costs really come from, and how design, materials, and manufacturing choices affect reliability long after the first prototypes ship.

1. When Rigid Boards Stop Working: Why Flex PCBs Enter the Picture

The first time a rigid board becomes the problem, it’s usually obvious. One compact control module for an industrial sensor failed vibration testing after a few hours. The electronics were fine. The connectors weren’t. Replacing the cable assembly helped for a while, but the failure came back under thermal cycling between roughly -20°C and 70°C. The issue wasn’t signal integrity or layout density. It was mechanical stress.

That’s the moment many teams start talking to a flex PCB manufacturer, often later than they should. Flexible circuits were originally used to replace wire harnesses, but in practice, they solve a broader set of problems: dynamic movement, tight packaging, and tolerance stack-up that rigid boards simply can’t absorb.

What catches people off guard is that flex PCBs aren’t just “bendable boards.” They’re a different mechanical system. Copper thickness, bend radius, adhesive choice, and even solder mask strategy change how the circuit survives repeated flexing. One project showed cracking near pad edges after about 900–1100 bend cycles. The copper was fine. The coverlay opening wasn’t.

A capable, flexible PCB manufacturer doesn’t just fabricate what’s on the Gerber. They push back on stack-up choices, ask how often the circuit moves, and want to know if the bend is static or dynamic. That conversation usually saves at least one redesign.

2. Flex PCB vs. Rigid PCB: A Numbers-Driven Comparison

From a cost spreadsheet perspective, flex PCBs look expensive. Unit pricing is often around 2.5–3.5× higher than standard FR-4, depending on layer count and yield. That part is true. What gets missed is system-level cost.

In builds where a rigid PCB plus two connectors and a cable assembly are replaced by a single flex circuit, assembly time typically drops by 20–35%. Error rates fall, too. Manual wiring mistakes don’t disappear entirely, but they become rare.

Weight and volume matter as well. In one handheld device, switching to a flex interconnect shaved roughly 18–22% off internal volume. Thermal behaviour changed, too. The board ran a bit warmer locally, but airflow improved enough that overall temperature stayed within limits.

Here’s a realistic comparison seen across multiple programs:

| Initial board cost | Lower | Higher (≈2.5–3.5×) |

| Assembly time | Longer, manual steps | Shorter, fewer operations |

| Failure points | Connectors, crimps | Mainly solder joints |

| Mechanical tolerance | Low | High |

For teams comparing flex pcb manufacturers, these trade-offs usually matter more than raw board pricing.

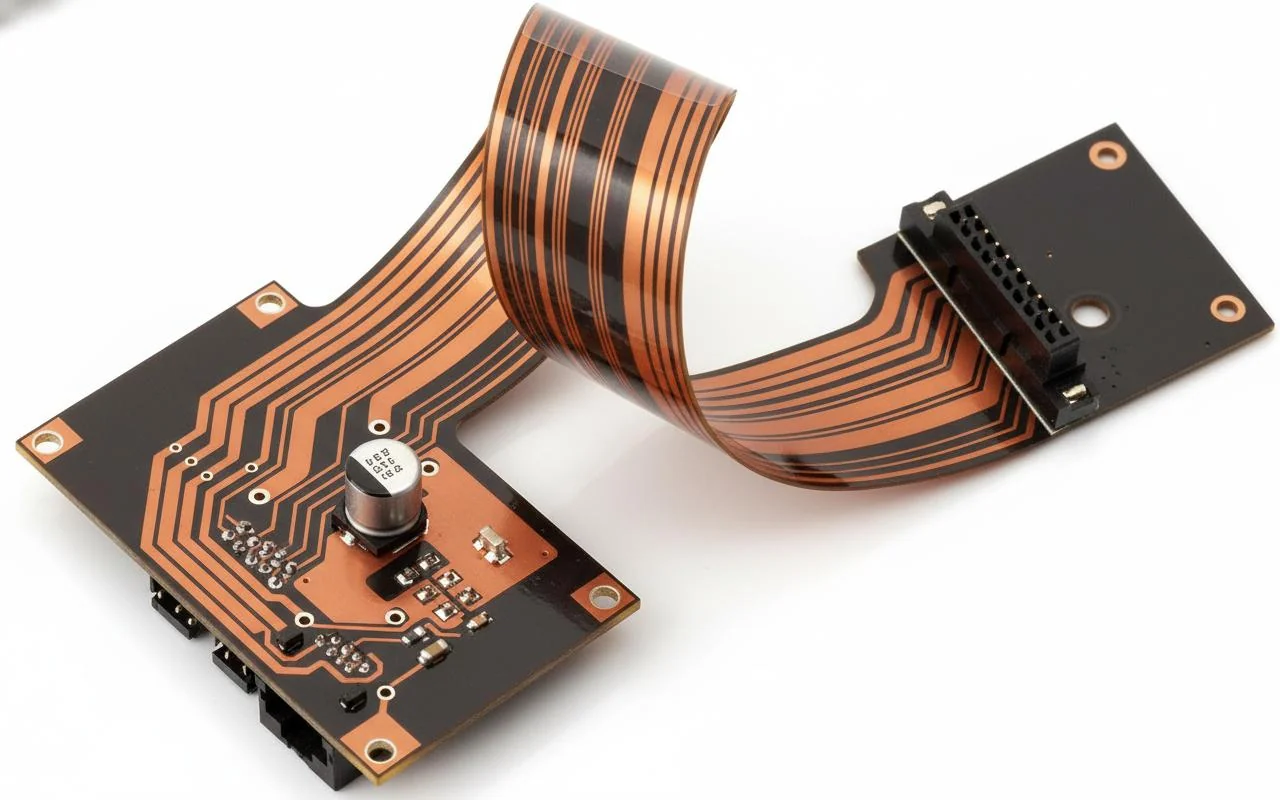

3. What Is a Flex PCB, Really?

So, what is flex PCB beyond the marketing definition? At its core, it’s a copper circuit laminated onto a flexible dielectric, most commonly polyimide, designed to survive bending without cracking or delaminating.

The key difference isn’t flexibility alone. It’s controlled flexibility. Areas meant to bend are engineered differently from areas meant to mount components. That distinction separates a reliable flex design from one that fails quietly after a few months.

- Base material is usually polyimide, typically 12.5–25 µm thick.

- Copper is often rolled annealed (RA), not electrodeposited.

- Protection comes from coverlay, not standard solder mask.

- Bend radius is calculated, not guessed.

A flexible PCB manufacturer evaluates these elements together. Treating flex like thin FR-4 almost always causes problems later.

4. The Most Common Mistake: Designing Flex Like Rigid

This shows up constantly. Designers route tight 90-degree corners, place vias in bend zones, and spec 2 oz copper everywhere “for safety.” The board passes electrical tests. Mechanical testing tells a different story.

Thicker copper increases current capacity, but it also raises stiffness dramatically. In dynamic flex applications, 1 oz copper might survive 800–1200 cycles. Jumping to a 2-oz can can cut that in half, depending on bend radius and laminate quality.

Another issue is placement. Through vias in flex areas introduce stress risers. Testing 200+ units on one project showed cracking initiated via barrels, not traces. Moving the vias out of the bend zone solved it without changing materials.

Good flex pcb guidelines exist (IPC-2223 is a starting point), but experienced manufacturers go further. They’ll flag pad shapes, recommend teardrops, and suggest stiffeners only where they’re actually needed.

5. Materials That Make or Break a Flex PCB

Polyimide dominates flex PCB materials for good reasons. It handles heat, resists tearing, and stays dimensionally stable during reflow. That said, not all polyimide behaves the same.

Adhesive-based laminates are cheaper and easier to process. Adhesiveless constructions cost more but reduce Z-axis expansion and improve high-temperature reliability. In lead-free assembly, that difference matters.

Copper choice is another trade-off. Rolled annealed copper bends better but costs more and has longer lead times. Electrodeposited copper works for static flex, but dynamic applications push its limits.

Suppliers like WellCircuits usually stock multiple material systems, but availability depends on region and volume. A flexible PCB manufacturer in China might offer aggressive pricing, while a flexible PCB manufacturer in the UK often focuses on shorter turns and lower MOQs.

6. Flex and Rigid-Flex Stack-Ups: More Options Than People Expect

Single-layer flex is common, but it’s only part of the picture. Double-sided and multilayer flex circuits handle denser routing at the cost of stiffness and complexity.

Rigid-flex adds another layer of decisions. Bonding rigid FR-4 sections to flex cores introduces CTE mismatch. That’s manageable, but only if the stack-up is designed with it in mind.

A typical rigid-flex failure shows up after thermal cycling. Copper cracks near the rigid-to-flex transition. Adjusting fillet geometry and extending the coverlay usually helps, but it’s not automatic.

Not every flex rigid pcb manufacturer supports high layer counts. Many cap at 6–8 layers reliably. Beyond that, yields drop and costs climb quickly.

7. Manufacturing and Assembly: Where Theory Meets Reality

Flex PCB manufacturing looks straightforward on paper. In practice, handling thin material is the hard part. Panels warp. Registration shifts. Yield loss happens.

Coverlay alignment is a common pain point. Openings that are slightly off can expose copper edges, leading to corrosion over time. ENIG helps, but black pad risk still exists if process control slips.

Assembly brings its own challenges. Flex circuits move during reflow unless properly fixtured. That adds cost and limits which assembly houses can handle the job.

This is where choosing the right flex pcb manufacturer matters more than chasing the lowest quote.

8. Where Flex and Rigid-Flex Circuits Actually Get Used

Flex PCBs show up anywhere space, motion, or reliability collide. Medical devices use them to reduce wiring errors. Automotive systems rely on them, where vibration would destroy connectors.

Industrial equipment often adopts flex reluctantly, usually after repeated field failures. Once implemented correctly, the failure rate drops, but the learning curve is real.

Not every application needs flex. Static enclosures with plenty of room are better served by rigid boards. Flex earns its place when mechanical constraints dominate electrical ones.

Understanding that boundary helps teams work more effectively with flex pcb manufacturers—and avoid paying for flexibility they don’t actually need.

9. Rigid-Flex Isn’t Just “Flex Plus Rigid”: Where Designs Usually Go Wrong

The most common mistake seen in rigid-flex designs happens early: treating the flex portion like a cable and the rigid portion like a normal FR-4 board, then stitching them together. On paper, that works. On the shop floor, it often doesn’t.

One controller board combined two rigid sections with a dynamic flex hinge rated for a few bends per day. Assembly yield looked fine at first, around 95–96%. Field returns started after three months. Cracks showed up right at the rigid-to-flex transition. The root cause wasn’t copper fatigue. It was the stack-up. The rigid section used 1.6mm FR-4 with 2oz copper, while the flex tail dropped abruptly to 0.5oz. That stiffness jump concentrates stress right where you don’t want it.

A capable flex rigid PCB manufacturer will usually push for stepped copper reduction, larger fillets at the transition, or a “bookbinder” style layup that smooths the mechanical gradient. IPC-2223 touches on this, but the standard doesn’t replace judgment. If the board sees vibration above roughly 6–8g RMS or thermal swings wider than 60°C, those transition details matter more than trace width optimisation.

Rigid-flex solves connector reliability and packaging issues, but it’s unforgiving. Once laminated, fixes are expensive. That’s why experienced manufacturers insist on bend diagrams, not just Gerber’s.

10. Assembly Yield: Why Flex Boards Fail After Fabrication

Fabrication success doesn’t guarantee assembly success. That distinction gets missed, especially when teams move from rigid boards to flex without changing their PCBA strategy.

During one pilot run of about 150 units, electrical test pass rates were fine. Assembly yield wasn’t. Components near the flex area showed tombstoning and occasional pad lifting during reflow. The profile was copied from a rigid board build. That was the mistake.

- Flex materials heat faster; polyimide doesn’t behave like FR-4.

- Uneven support during reflow allows the flex to sag.

- Stiffeners placed too close to pads create localised stress.

Most flexible PCB manufacturers recommend palletised reflow or temporary carrier boards. It adds cost and setup time, but yields usually climb from low-90% into the 96–98% range once the process stabilises. Not perfect, but predictable.

This is where collaboration matters. Shops like WellCircuits often flag assembly risks during DFM review, not because the layout is “wrong,” but because it’s incompatible with standard assembly lines.

11. What Separates a Real Flex PCB Manufacturer from a Generic Board Shop

Plenty of board houses claim flex capability. Fewer can do it consistently.

Flex and rigid-flex fabrication demands tighter process control: laser drilling for microvias in thin polyimide, adhesive flow control during lamination, and coverlay registration that’s usually held within ±75–100µm. Miss that, and pads get exposed or constrained.

Quality manufacturers track these variables lot by lot. That includes copper elongation data, not just thickness. Rolled annealed copper behaves very differently from electro-deposited copper under repeated flexing. If a supplier can’t tell you which one they’re using, that’s a warning sign.

Certifications matter, but context matters more. IPC-6013 Class 2 is common for consumer electronics. Medical or aerospace programs often require Class 3, along with tighter bend radius rules. Not every flex PCB manufacturer is equipped for that level of control, even if they’re ISO 9001 certified.

12. Cost Drivers in Flex and Rigid-Flex: Where the Money Really Goes

Flex circuits cost more than rigid boards. That’s not news. What surprises teams is where the cost actually comes from.

Material is only part of it. Polyimide itself isn’t cheap, but the bigger drivers are process steps: multiple lamination cycles, laser drilling, coverlay application, and yield loss from handling thin cores.

| Layer count | +20–35% per added layer | Flex multilayers scale poorly vs rigid |

| Rigid-flex transitions | +15–25% | Extra lamination and routing steps |

| Tight bend radius | Variable | Often forces rolled annealed copper |

Cost-effective designs usually simplify early. Single or double-sided flex works for many applications under 1–2A per trace. Multilayer flex up to 20 layers exists, but it’s rarely justified unless space or reliability leaves no alternative.

13. Flex PCBs and Emerging Products: What’s Changing

Data from recent builds shows flex content increasing in compact devices, especially where space and weight matter more than raw cost. Wearables, handheld medical tools, and small robotics modules all push in that direction.

The trend isn’t just thinner boards. It’s integration. Rigid-flex replaces multiple rigid boards and connectors with a single assembly. That improves shock performance and reduces tolerance stack-up, but it shifts complexity upstream into design and fabrication.

High-speed signals add another layer. Under about 1–2GHz, high-Tg FR-4 sections mated with standard polyimide flex usually work. Above that, impedance control through the flex becomes touchy. Dielectric constant variation across vendors can be ±10%, which shows up as skew or reflection if not modelled.

This is where experienced flex PCB manufacturers earn their keep. They don’t promise miracles. They flag risks early and suggest compromises that keep the project buildable.

14. Quality Systems, Testing, and What They Don’t Tell You

ISO and IPC certifications are table stakes. They tell you a process exists. They don’t tell you how it behaves under stress.

Flex-specific testing matters more: bend testing, thermal cycling, and adhesion checks after humidity exposure. One batch of flex tails passed the electrical test but failed the peel strength after 85% RH storage. The adhesive system was marginal. Paperwork didn’t catch it.

Ask how often a manufacturer runs destructive tests and whether results are trended. The good ones do. They’ll also be upfront about limits, like minimum bend radius for a given stack-up or maximum panel size before yield drops.

15. Getting Started Without Burning a Revision

The fastest way to lose time is to treat a flex PCB manufacturer like a commodity vendor. Upload files, wait for a quote, hope for the best. That approach usually costs one extra spin.

Early conversations help. Share how the board moves, how often it bends, and where it’s constrained. Even rough information beats assumptions. Flexible PCB manufacturer China options can be cost-effective for volume, while local or regional suppliers help during prototyping. It depends on priorities.

If you need a starting point, companies like WellCircuits typically respond within a day, but the real value is the engineering feedback that comes after. That’s what keeps flex designs from failing quietly six months later.

Flex and rigid-flex PCBs earn their place when mechanical stress, space constraints, or assembly complexity become the real problem—not when a design just feels “advanced.” The details matter: material selection, stack-up choices, bend geometry, and how assembly is handled all influence whether a flex circuit survives 1,000 cycles or fails at a few hundred. Higher unit cost is part of the equation, but system-level savings often show up in reduced connectors, faster assembly, and fewer field issues.

The practical next step isn’t jumping straight to a flex redesign. It’s reviewing where your current rigid solution is struggling—vibration points, connector failures, thermal movement—and mapping those to flex-specific constraints. A capable flex pcb manufacturer will push back on risky assumptions early, which is usually cheaper than fixing cracks and yield losses later. That conversation, done at the concept stage instead of after EVT, is where flex starts paying for itself.

About the Author & WellCircuits

Engineering Team

Senior PCB/PCBA Engineers at WellCircuits

Our engineering team brings over 15 years of combined experience in PCB design, manufacturing, and quality control. We’ve worked on hundreds of projects ranging from prototype development to high-volume production, specialising in complex multilayer boards, high-frequency designs, and custom PCBA solutions.

About WellCircuits

WellCircuits is a professional PCB and PCBA manufacturer with ISO9001:2015 certification and UL approval. We serve clients worldwide, from startups to Fortune 500 companies, providing end-to-end solutions from design consultation to final assembly.

Experience

15+ Years

Certifications

ISO9001, UL, RoHS

Response Time

24 Hours

Quality Standard

IPC Class 2/3

Need PCB/PCBA Manufacturing Support?

Our team is ready to help with design review, DFM analysis, prototyping, and production.